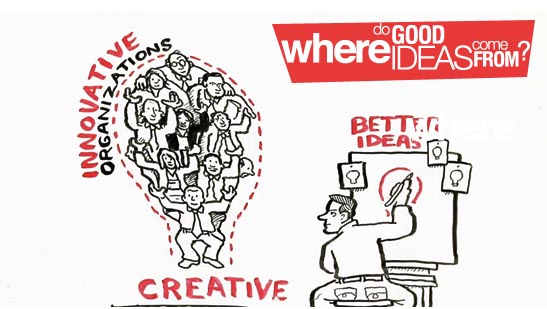

We take ideas from other people, from people we’ve learned from, from people we run into in the coffee shop, and we stitch them together into new forms and we create something new. That’s really where innovation happens. And that means that we have to change some of our models of what innovation and deep thinking really looks like, right. I mean, this is one vision of it. Another is Newton and the apple, when Newton was at Cambridge. This is a statue from Oxford. You know, you’re sitting there thinking a deep thought, and the apple falls from the tree, and you have the theory of gravity. In fact, the spaces that have historically led to innovation tend to look like this, right. This is Hogarth’s famous painting of a kind of political dinner at a tavern, but this is what the coffee shops looked like back then. This is the kind of chaotic environment where ideas were likely to come together, where people were likely to have new, interesting, unpredictable collisions — people from different backgrounds. So, if we’re trying to build organizations that are more innovative, we have to build spaces that — strangely enough — look a little bit more like this. This is what your office should look like, is part of my message here.

And one of the problems with this is that people are actually — when you research this field — people are notoriously unreliable, when they actually kind of self-report on where they have their own good ideas, or their history of their best ideas. And a few years ago, a wonderful researcher named Kevin Dunbar decided to go around and basically do the Big Brother approach to figuring out where good ideas come from. He went to a bunch of science labs around the world and videotaped everyone as they were doing every little bit of their job. So when they were sitting in front of the microscope, when they were talking to their colleague at the water cooler, and all these things. And he recorded all of these conversations and tried to figure out where the most important ideas, where they happened. And when we think about the classic image of the scientist in the lab, we have this image — you know, they’re pouring over the microscope, and they see something in the tissue sample. And “oh, eureka,” they’ve got the idea.

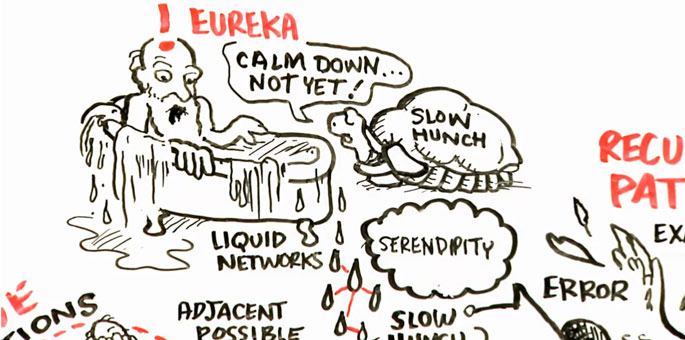

What happened actually when Dunbar kind of looked at the tape is that, in fact, almost all of the important breakthrough ideas did not happen alone in the lab, in front of the microscope. They happened at the conference table at the weekly lab meeting, when everybody got together and shared their kind of latest data and findings, oftentimes when people shared the mistakes they were having, the error, the noise in the signal they were discovering. And something about that environment — and I’ve started calling it the “liquid network,” where you have lots of different ideas that are together, different backgrounds, different interests, jostling with each other, bouncing off each other — that environment is, in fact, the environment that leads to innovation.

The other problem that people have is they like to condense their stories of innovation down to kind of shorter time frames. So they want to tell the story of the “eureka!” moment. They want to say, “There I was, I was standing there and I had it all suddenly clear in my head.” But in fact, if you go back and look at the historical record, it turns out that a lot of important ideas have very long incubation periods — I call this the “slow hunch.” We’ve heard a lot recently about hunch and instinct and blink-like sudden moments of clarity, but in fact, a lot of great ideas linger on, sometimes for decades, in the back of people’s minds. They have a feeling that there’s an interesting problem, but they don’t quite have the tools yet to discover them. They spend all this time working on certain problems, but there’s another thing lingering there that they’re interested in, but they can’t quite solve.

To find out more about how innovation happens, watch the informative 2 videos below!

Leave a Reply